Garbáty Zigarettenfabrik

Cigarette factory up in smoke

The story behind the Garbáty’s Zigarettenfabrik is one of Nazi persecution, East German indifference, and shameful greed bringing the systematic destruction of a family enterprise.

It may not be abandoned anymore, but for a time the former cigarette factory In Pankow was allowed wallow in neglect and decay, home only to tragic memories.

Everything was long gone by the time I stumbled up the steps to where a huge expansive room greeted me, a cavernous hall lit by a thousand sunny windows, bereft of any furnishings or curiosities. It was 2010 and I was too late. It was industrial without the industry.

I found more of the same on each floor as I made my way up. Brick walls, pillars, smooth clean floors and disconcertingly clear windows providing no clues to its turbulent past, nichts.

Instead there were just the tell-tale signs of “progress” – a glut of diggers, construction paraphernalia and scaffolding scattered around, evidence of the poor building’s fate.

Josef Garbáty-Rosenthal began producing tobacco products with his wife Rosa Rahel at home in 1879, opening a factory on Linienstraße in Mitte two years later.

They later expanded to facilities on Schönhauser Allee before moving to a more suitable factory on Berlinerstraße in Pankow in 1906. Pankow was an independent town at the time.

The factory had had 800 employees the following year, with both the Kurmark and Königen von Saba brands proving very popular, according to Beate Meyer in her book Jews in Nazi Berlin.

Meyer writes that Josef transferred the company to his sons Eugen and Moritz in 1929, and the former sold his 50 per cent share to the big-shot Reemtsma brand, which controlled more than 60 per cent of the market at the time.

Following the Nazis’ rise to power in 1933, Der Stürmer repeatedly denounced Kurmark cigarettes as a “Jewish product” before the Nazi-fawning antisemitic tabloid declared: “The Garbáty cigarette factory is a purely Jewish firm.”

Moritz Garbáty received threatening letters and was then accused of smuggling foreign currency. Cue a dreaded Gestapo investigation.

Reich economics minister Hermann Göring instructed Jewish firms’ import quotas to be reduced. Garbáty’s quota dropped by ten per cent in January 1938.

Competitors jumped on the bandwagon, breaking the company’s regular supply to customers. Turnover practically halved between 1937 and 1938.

Moritz Garbáty saw no option but to sell the firm, and his lawyer opened negotiations with interested Aryan parties.

Dr. Jakob Koerfer’s consortium included Emil Georg von Stauss, prominent Nazi supporter and director of Deutsche Bank with excellent connections, including Göring himself. It was simply a matter of how little the Garbáty family would get.

Reemtsma didn’t dare rock the boat and sold his 50 per cent to Koerfer for six million Reichsmark. Various institutions were pushing for the rapid Aryanization of the firm, which was losing value by the day as the political climate worsened. Anti-Semitism was sending the value of Jewish companies plummeting.

Moritz Garbáty signed over the firm – valued at RM 31.6 million on Dec. 31, 1937 – to Koerfer and his Aryanizers on Oct. 24, 1938.

The contract stated that he was to be given for RM 6 million in compensation, with his brother Eugen to get one million. The Aryanizers were to pay a further RM 1.74 million for the factory premises in Pankow.

Meanwhile, the Reich economics ministry had to finalize the transaction, allowing Judenreferent Alf Krüger to peremptorily lower the RM 6 million payment to RM 4.11 million.

Koerfer transferred the funds on Nov. 8 into a middleman’s bank account, a loophole to get around the German foreign exchange’s blocking order, which would have blocked Moritz from accessing his account if the payment had been made directly, according to Meyer.

The contract was concluded around the days of the November pogrom, which saw the violent persecution, arrests and beatings of Jews. At least 91 were killed on the nights of November 9-10. Moritz Garbáty had to go into hiding. His wife and 8-year-old son found refuge in a taxi traveling through Berlin:

“My mother rang home (from a friend’s house) to see what the situation was like,” Thomas Garbáty told Meyer in an interview in 1999.

“Our housekeeper Elise answered the phone. ‘Elise, how are things at home?’ asked my mother. The answer was, ‘I’m sorry but Mrs. Garbáty is not here.’ Then we knew that the Gestapo were in the apartment. They were looking for us. It was Kristallnacht.”

Jews with money could obtain exit visas by making a compulsory “donation” to the chief of police. Moritz and Eugen Garbáty paid Wolf-Heinrich Graf von Helldorf RM 1.15 million in total. He was involved in the plot to assassinate Hitler some years later and consequently hanged.

Jews were also forced to pay ‘compensation’ for the pogrom damage through another compulsory voluntary donation. Moritz Garbáty coughed up RM 20,000. A property levy accounted for RM 1.12 million, an emigration tax RM 1.43 million. A further RM 830,000 went on extortionate foreign exchange rates. He was left with 861 Reichsmark. This too was confiscated for the German Reich.

Moritz Garbáty, his wife Ella and son Thomas managed to escape to New York via Amsterdam and Bordeaux, arriving finally on June 9, 1939. (Thomas later became a respected professor of medieval English at the University of Michigan.)

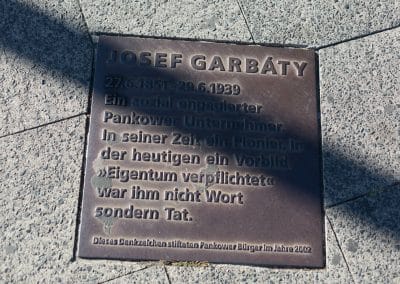

Josef Garbáty-Rosenthal, 87-years-old, had stayed behind. He died three weeks later, on June 29, shortly before the outbreak of the war.

The Königin von Saba and Kurmark cigarettes were replaced with inferior ‘war brands’ in 1942. There was very little quality tobacco available anymore.

The factory was badly damaged in the Battle of Berlin in April 1945. Its new owner, Jacob Koerfer, had already fled to Switzerland in 1944.

The business was appropriated after war’s end by the East German regime. The factory continued to produce cigarettes, was renamed VEB Garbáty in the 1950s when it began producing the Club brand, and it merged with VEB Josetti to form the Berliner Zigarettenfabrik in 1960.

The fall of the Berlin wall spelled the end. The factory was taken over by the infamous Treuhand agency set up to oversee the privatization of East German companies, assets and enterprises.

The Club brand was sold off to the RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company for just 10 million marks on Oct. 2, 1990, a day before German reunification when it would have been illegal. The last cigarettes rolled off the production lines in September 1991 and all the furnishings, machines and fittings were sold to the Lübecker Zigarettenfabrik. The workers were all let go. The Garbáty Zigarettenfabrik was no more.

There were techno parties in the heady years following reunification, but it was only so long before Berlin’s building boom took its toll.

Now the Garbáty Zigarettenfabrik is home to luxury apartments. The builders used the nice part of its history as a selling point – a final insult for the Garbáty family, which was never compensated, not even after the war.

LOCATION AND ACCESS (HOW TO FIND GUIDE)

- What: Garbáty Zigarettenfabrik (cigarette factory).

- Where: Berliner Straße 120/121 and Hadlich Straße, 13187, Berlin-Pankow.

- How to get there: Get the S2 S-Bahn from Friedrichstraße to Pankow, or the U2 (say hello to Bono if he’s driving) from Alexanderplatz. It’s just a two-minute walk north from the station, on the right hand side. Here’s a map in case you get lost.

- Getting in: You won’t be able to get in now unless you’re one of the residents, unless you know one of the residents, or unless you plan on breaking in and stealing something from the residents. There are still abandoned places nearby you can visit instead, such as the Iraqi embassy, Güterbahnhof Pankow, or Pankow Schwimmhalle.

More stories of Nazi persecution

Kraftwerk Vogelsang

Kraftwerk Vogelsang is a powerless power plant. People gave their lives building it and fighting over it. Now that they’re gone, nobody wants it at all.

SS Bakery

The SS Bakery only went bust when the Nazis did. They forced prisoners from nearby Sachsenhausen to make bread to keep other concentration camps going.

Luna-Lager bunker

A wartime bunker is all that’s left of the former Luna-Lager labor camp at Schönholzer Heide, now a grassy, pretty wild and pleasant 35-hectare park.

There used to be parties in this building, at least in the courtyard in the summer. I guess it would have been in 2003 or 4…

This location is ‘over’! They make some lofts inside…

I know – it’s a shame. You need to move quickly to enjoy these wonders before they’re ruined by modern banalities.

IT’S PASSED – from now on, there are people living there inside, you can not visit it anymore.

REST IN PEACE

Thank you very much for this report. My great-grandfather worked in this factory from roughly 1906 to 1926, and I’ve been trying to reconstruct his experience for a book. I visited the factory a few years ago, but never made it inside. This was very helpful.

I have some great stories from inside this factory if you would like to hear them.

Hey AJB, would love to hear your stories man. Get in touch!

I think everyone wants to read your grandpa’s story, AJB.

Fantastic article, Irish Berliner, thank you for sharing your explorations.

Wow! my German teacher is a Garbaty. he would always tell us stories of how his dad escaped Nazi Germany. Funny to think it’s now an apartment complex.

Garbaty was also a factory in Kreuzberg auf der Cuvrystrasse and produced Kurmark there for many years, shipping that brand weekly to the southwest of Germany around Sigmaringen, the only area where Kurmark was still sold, even after it was merged with British American Tobacco (BAT), the company that also makes HB. Spent many hours at Cuvrystrasse! May dad was the shipping manager!

Wow! Thanks for the comment. Would love to hear more!!