Teufelsberg Tale

Remembering life at Field Station Berlin

While Berlin wrings its hands over what to do with Teufelsberg, many veterans who served on the site are watching with interest from afar. After all, those who worked at Field Station Berlin were trained to watch with interest from afar.

Lew McDaniel in 1967 during his time at Monterey, California.

Lew McDaniel, of West Virginia, USA, was one of those stationed here between 1968-71, when he worked as a linguist.

He helped organized a reunion of his colleagues in Berlin for the 50th anniversary of the first permanent spying facilities (SIGINT) on the hill in September 2013, when they placed a replica of a commemorative plaque at the site. In Morse code dots and dashes, it states “In God we trust, all others we monitor.”

“It wasn’t an official motto, just one we troops came up with,” McDaniel told Abandoned Berlin. “My favorite is from another installation along the Czech border: ‘First to know, first to glow.’”

The veterans hope one day they’ll be allowed place a permanent bronze plaque at the site.

McDaniel was happy to share some (though not all!) of the details of happier times at the spy station in its heyday.

What follows below is McDaniel’s account of life at Field Station Berlin as told in his own words to Abandoned Berlin.

Secrecy

This is all sort of difficult to discuss since we are still bound by oaths of the time. While the NSA admits it had a presence in Berlin, details are still cloaked. That presence was about 100 of us service types for every one of the (NSA headquarters) Fort Meade folks and without us a great deal would have never been known. They get the credit; we did the work.

While there were certainly very around-the-clock busy times several times a year coinciding with military exercises, I don’t recall during my time any ‘uh oh, the balloon is going up’ incidents. Guys stationed there during the Czech invasion, initial construction of the Wall, and some of the air space issues – they were in tense situations. Nonetheless, anything out of the ordinary sharpened our attention.

We were aware of the situation around us, but really didn’t think about it that much. If we talked about it, conversations were usually humorous in some macabre way. I would say we were more aware of the situation around us in East Germany than troops in other units in Berlin, as well as Berlin citizens.

Encounters

For us, it was strange to actually physically see the opposition. I doubt that I saw VoPos (Volkspolizei, the East German police) or Soviet troops more than 10 times during my tour in Berlin. Some were guards at the border where the American duty train changed locomotives. Though forbidden to do so, some traded Playboys and cigarettes and such for articles of Soviet uniforms. I have an East German flag obtained that way. Once in a while, we would see Soviet troops visiting the PX (American military retail store) on Clayallee.

I took some slides of a building just east of the Glienicke Bridge. I was wandering around in that area when I noticed people moving around in the upper stories of a building in the wall and apparently abandoned. I also noticed the windows seemed to be cut straight across. When I got my camera up to take the picture, the people moved away from the windows.

This, I think, is the closest I physically came to the opposition at work (other than the train guards). The building turned out to be an observation post watching US Military liaison mission cars come and go to/from West Berlin.

I think I have to say our mission was somewhat more abstract than that of regular line troops like infantry, armor, artillery folks. Sure, we were trained in basic training like everyone else to fire rifles and such but after that we fired a weapon once a year. Regular line troops did that regularly. In a sense, we were sort of scouts ahead of the cavalry so to speak.

Berlin

It was remarkable to me to see the effects of WWII – houses missing, others pockmarked with bullet holes, the Gedächtniskirche. And I was always aware of what rested under our site. (An unfinished Nazi military training college.)

Years later, my father-in-law and I discussed the city. His view as a WWII B-17 waist gunner on night bombing runs was of course much different.

MOUNTAIN MYTHS

I am sure you have seen all the various T-Berg links on the web. There are a lot of them, some accurate and some not. No submarine tunnel, a favorite while I was there, no aircraft radar, and no secret escape tunnels.

The first site on T-Berg consisted of mounted vans in the early 1960s or thereabouts. I am not sure when the first dome was built, but I think around 1963. During my time there, there was a single dome with metal structures radiating from it. I worked in one of them – hot in summer with no windows we could open and so cold in winter we wore coats, sweaters, and gloves. Gloves made typing very difficult so I cut the tips of the fingers out of mine.

THE BENDS

The dome was two stories atop a concrete central pillar. The dome was made of some kind of rubberized canvas and kept inflated by air compressors from a WWII German submarine. At times the wind would overpower the compressors’ capacity. When that happened, the windward dome side would partially collapse, causing a klaxon to sound. Upon hearing it, we all got outside and away from the structure as quickly as possible lest the dome fall and take everything in it down. The normal air pressure inside the dome was high enough that technicians who had to work occasionally in the top part actually had to decompress on the way out to avoid ‘the bends.’

Grunie pigs

The view from the surface of the Berg (hill) itself was phenomenal on a clear day. At night, we often saw flares firing off along what was then the Wall on the western border of West Berlin. Most of the time, it was caused by animals tripping the flare trigger. Near the site, we often saw wild boars along the perimeter fence.

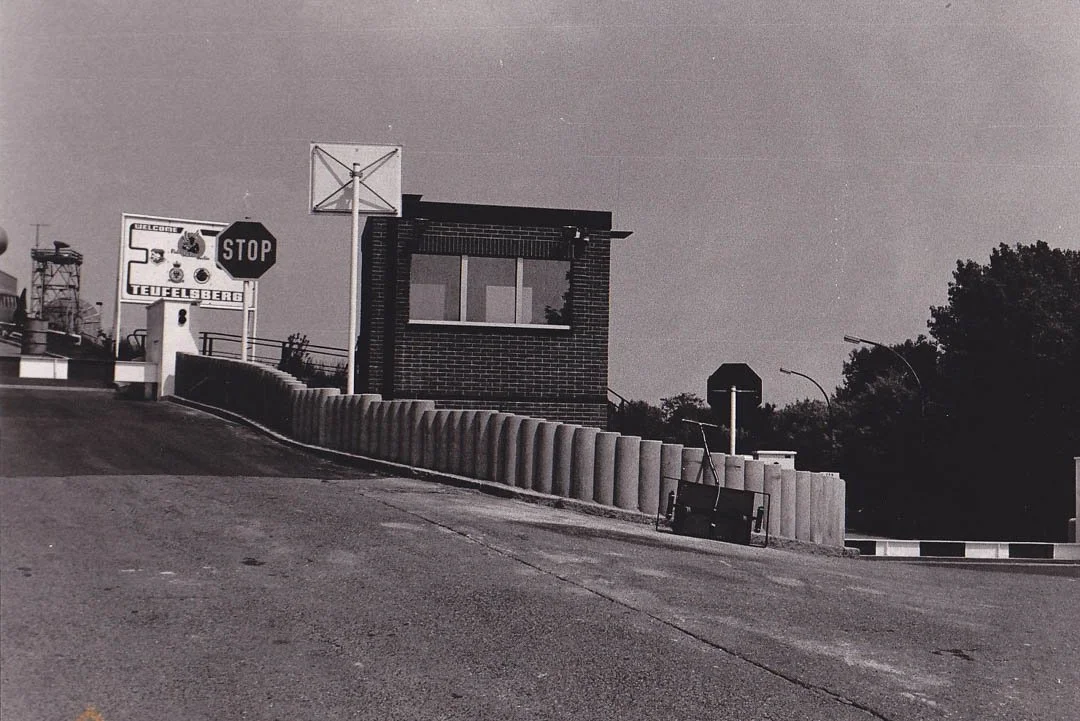

NO PHOTOS

We were cautioned to not be photographed if we could help it. However, Soviet mission cars were in the Grunewald area a great deal and photographed away when they wanted. They were pretty easy to spot – black low grade Mercedes with diplomatic plates and RDF antennae on the roof.

ACTIVITIES

Work there was a mix of excitement at times, coupled with normal business at others. For most of my time there, I worked around the clock regardless of shift when there was urgent work to be done. I remember several three-week stints when I barely bothered to leave. Usually there was an even flow of things to learn and look out for that made the work very interesting – had my wife at the time not wished otherwise, I would have remained in the Army for a career.

TARGETS

We were keenly aware the Soviets and the East Germans considered T-Berg a prime, first shot target and could have readily obliterated us. Berlin was after all within very easy striking distance of several Soviet tank, artillery, and rocket divisions. Teufelsberg would have literally been vaporized within less than a second after the command to fire was given and that command would have been one of the first.

We were a military installation with concordant rules and regulations, but for the most part we were left alone to do our jobs. While we were certainly in the Army, wore the uniform, and followed the rules for the most part, we did not feel like we were part of the ‘regular’ army that toted rifles and slept in tents and such. I don’t mean to sound like a snob, but our talents were more suited to what we did than to being regular line troops.

PARTIES

We were also dedicated partiers and nightlife people. We worked rotating five-day shifts and at end of the five days, many folks headed for the bars or to gatherings. Not many folks left Berlin – we could only travel via the American or British duty train or via American flagged aircraft and were not allowed in East Germany or East Berlin – so leaving the city was time consuming.

STEGLITZ

We lived in an apartment in Steglitz, so I was not subjected to life at Andrews Barracks where most were quartered, other than the first week I was in Berlin. My original assignment after language school was to the US Military Liaison Mission in Potsdam. However, the Army realized shortly after that that I was married and changed the orders. Married personnel were not posted to Potsdam.

Living on Maßmann Straße in Steglitz was interesting. I was issued two weeks of C-rations in case the balloon went up and given an airline ticket for my wife for the same situation. I always felt neither would be of any use – see the comments above regarding the forces around Berlin. When I departed Berlin, I had to turn in the rations and the ticket.

NEIGHBORS

The folks who lived in the other apartments there were nice. We were invited to their parties and family events and we often reciprocated. The Hauswirt and her husband were Czechs who came to Berlin before the Wall was built. We often took them cigarettes, bourbon, and beef and they cooked Czech meals for us now and then. We downed copious quantities of excellent Rumtopf they seemed to always be making

Before that, we lived on a street over off Clayallee in a house that belonged to an old couple who had lived there through WWII. They said their house was occupied at one time by Russian troops who were civil enough, but didn’t seem accustomed to a regular house.

CAREER

What we did and how we did it remains cloaked in secrecy still. I can tell you the Army was in dire need of Russian linguists when I signed up in 1967. Which I did after receiving my draft (conscription) notice – draftees during the Viet Nam war did not usually have a choice of what they did in their two years in the Army, so I enlisted for four years in order to get a better opportunity to do something interesting. I originally wanted to be a helicopter pilot, but discovered during testing for that that I am colorblind and that disqualified me… So I was asked if I wanted to be a linguist. I said sure, how about German, since I had four years of German courses in college. But they needed Russian linguists and sent me to the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California for nine months. Last time our vets group held a reunion at the institute, Middle Eastern language courses were the largest group – not much Russian taught there now that the Cold War is over.

PRANKS

’Cold War’ is a broad brush that paints over numerous interesting aspects of that time and place.

Humor – a saving grace for us all – had its place as well. There is a tale you may have read about the stovepipe mortar. Reportedly – and there are several who claimed to have witnessed the events and many who don’t believe them – the following happened at one of our sites in the southeastern part of the city immediately next to a VoPo guard tower by the wall. The guards kept a close watch on the site, prompting some jokesters to creep onto the building roof with a long piece of black stovepipe and a beverage bottle painted black. They carefully aimed the stovepipe toward the tower much as one would sight in a mortar. The guards watched closely.

One of the gang carefully raised up and dropped the bottle down the stovepipe like dropping a mortar round down the tube. The guards bailed out of the tower.

ALLIGATORS

I did not mention countless hours of endless boredom, depending on what your specific duties were. I was fortunate there was always something to catch my interest while others were not. Even so, there is nothing like 4 a.m. on a midnight shift after countless cups of coffee to make your mouth feel like an alligator camped in it.

Commies

Regarding our counterparts, we knew we were watched regularly. Soviet “mission cars” roamed the Grunewald near Teufelsberg regularly – black sedans with RDF antennae on the roof searching for radio signals from the site.

During one project I was on around 1970, we noticed the number of Soviet mission cars around the site had increased significantly. That's when we discovered our CRTs were radiating outside the fenced site perimeter. Had to shut down the project for a week or so until shielding could be put around our area.

We were also supposed to not let ourselves be photographed, beware of who we associated with, forbidden to go to East Berlin, had to fly in/out on American flag carriers, had to ride the American or Brit duty train to get in/out of the city.

Have been following the “what to do with TBerg” issue. Last I knew, there appeared to be some hope at least a portion of the site would be retained. Presumably the portion with the large radome and much “artwork.” I find it interesting that the site is used for commercials, gatherings, and concerts.

Memories

It has been 47 years* since I arrived in Berlin on the duty train in December. The only thing I recall about that day was the smell of coal burning in stoves and fireplaces. Other isolated recollections of my time there:

Summer evenings when it was sufficiently light to read outside at 10 pm.

Riding the Ubahn and Strassenbahn just to watch people. And a little old lady who stabbed the Umsteig I had dropped and took it as her own.

Folks strolling in the forests on sunny Winter days, often with their dogs.

Dining outside on the Kdamm on warm evenings.

A bar in the Tempelhof area where the street walkers hung out. Good food, strange people. There was also a pizza place near there called "The Dirty Old Man". White asparagus on the pizza he said he got out the ditches in the area.

Rosario's Pizza. We would make up an order on the Hill and someone would drive to Rosario's to pick it up. If we ordered three pizzas, we got a free bottle of Lambrusco which was often downed while returning to the Hill with the order. And yes, I made a few of those trips.

The NAAFI. Great single malts and cognac for very little money. I still have the Harris tweed jackets I bought there. They no longer fit, but I can't bring myself to give them away. They also ran "the NAAFI wagon" that came to the Hill at lunch time during the day. Excellent NAAFI wagon food, although I can't say the same for the NAAFI itself downtown...

Getting off the trick bus at Randy's on Finkensteinalle, heading inside, and not coming back out until 2 days later when the trick bus stopped to pick us up.

The hauswirt on Massmann Strasse where we lived. She and her husband were Czechs. I would bring them Jim Beam bourbon and beef. They would cook dinner for us and her family, after which we drank the bourbon...At the same location, our apartment opened onto a courtyard shared with other buildings. On pretty days, someone in the other building would play recordings of various operas. I am not an opera fan, but somehow that seemed just right.

Unrepaired bullet holes on the fronts of buildings in the various areas we lived. Missing structures removed by bombs in rows of apartments…

Listening to our landlord tell us about Russians living in his house near the end of the war.

Also at the Massmann Strasse location, the building had an inner courtyard. One very hot Summer day, I saw workers moving a piano into the courtyard near another entrance that led to the upper floors. They put a long wide canvas band around the forehead of one burly fellow who was bent over. Then they tipped the piano vertically onto the loop formed by the band. He stood up straight with the other guys balancing the piano on the band and against his back… Up the stairs he went, piano in the loop around his head with the other guys behind him… I got a fistful of beers from my fridge and followed them up three flights. They did not stop until they reached their destination. I handed out beers, which they really appreciated.

In my time there, I never ran into any male who would admit having fought in the West. East, yes. West, no.

We linguists didn't have to do much that was truly military. But once a year we did have to fire our weapons for record and we did have to be tear gassed. In basic training, there had been some debate about whether I was to be a linguist or, due to most excellent marksmanship, a LRRP (called a “lurp” – long range reconnaissance patrol, often a sniper).Fortunately languages won the day. Anyway, at one of our annual firings in Berlin, the fellow next to me managed to somehow get his rifle on full automatic which we were not supposed to do. He did not realize he had done it. When we began to fire, his rounds went high into a metal super structure over the range (automatic weapons rise when fired on full auto and you have to watch out for that) and ricochets went everywhere, sending us all diving to the ground. We remembered that the next year and no one would stand anywhere near him.

The day I left the Army, July 11, 1971, I mustered out at Ft. Dix NJ. I had not taken leave the entire 4 years of my service, so I was paid for that time – $6000+/- in cash. After mustering out, I went to the Philadelphia airport to await my flight home. Like many other GIs who were doing the same thing, we sat in a bar and waited for our flights. I noticed that every few moments, we all did the same thing – checked our pockets to make sure our money was still safe. The other day I was talking with a vet friend of mine who mustered out in Oakland, California and he related the same pocket checking going on when he was getting out.

Funny the things we remember.

McDaniel left the US Army after his three-year tour in Berlin was over. He taught Russian at West Virginia University for a while, and eventually retired as its computing director in 2000.

In 2015, when he first spoke to Abandoned Berlin, he was living with his wife 26 miles south of Morgantown, West Virginia, in the middle of a forest. They’ve since bought a place in town.

*It's a few more years now. McDaniel still follows TBerg developments from afar.

“Sure has been a twisting road.”

All photos (except those of Mr. McDaniel and the soldiers, which Mr. McDaniel himself provided) were very kindly provided by the US Army Intelligence & Security Command. Many thanks especially to Mike Bigelow for his assistance.

Filed 29/10/2015 | Updated 19/8/2024